Note: More refined estimates and better graphs are provided in this post, but the conclusions remain unchanged.

Scotland currently has four large conventional power stations. In descending order of capacity they are:

- Longannet - coal - 2.260 GW

- Torness - nuclear - 1.185 GW

- Peterhead - gas - 1.180 GW

- Hunterston B - nuclear - 0.965 GW

Longannet is scheduled to close in 2016, and the two nuclear stations by 2023. Between them they comprise 4.4 GW — about a third — of Scotland's generation capacity. So a question many might ask is:

Will there be a problem in meeting Scotland's electricity demand when these three power stations close?

(The data above comes from DUKES 2015 and unless otherwise stated other data given in this post comes from the Energy in Scotland 2015 (EIS) Scottish Government report.)

Sharing across the grid

The question is in fact based on a false premise. In reality, there is no Scottish demand met by Scottish electricity generation. A problem will only arise if demand across the whole GB national grid exceeds its supply of electricity from all power generation connected to the grid, and by inter-connectors to other countries.

That said, there are still reasons to consider the Scottish balance between supply and demand by estimating the amount generated and the amount used by consumers located in Scotland. One is political: the Scottish Government makes decisions on energy policy in Scotland. Another is economic: currently Scotland exports electricity and these sales bring benefits such as jobs and taxes raised in Scotland. So the "problem" mentioned in the above question may not be a lights out issue, but something more nuanced. Will the loss of these three power stations push Scotland into becoming an electricity importer with negative economic consequences? And if this happens, how does becoming dependent on decisions made in England and Wales sit with the Scottish government, and those who support independence? I'll leave that question hanging and concentrate on the facts and figures.

Great Scot!

Power is defined as energy flowing per second. 4.4 GW is a lot of power. It's roughly equal to each of these:

- 2 million standard kettles boiling

- 600,000 cars driving at urban speeds

- 4.4 million 1 kW electric bar fires

- Raising all water in Loch Lomond at 60 cm per hour*

- Two flux capacitors from Back to the Future's time travelling Delorean

* EDIT 30/3/16 — Originally I had this as 4 mph, but I'd got my sums wrong.

It is about a third of Scotland's current total generation capacity when the wind is blowing, and about half of it when it isn't. In terms of the entire GB grid, it is about 6% of total capacity.

Although there are plans for more generation capacity in Scotland by 2023, it's hard to estimate exactly how much because it depends on private companies deciding to invest and planning permissions being granted. However, the Scottish Government's target is to have 100% of gross consumption in Scotland (that's electricity, not deep fried Mars bars) equalled by renewable generation by 2020. By my estimates, this means Scotland will need to add 8 GW capacity of renewable generation by then, and almost all of that would be from new wind farms.

What follows assumes this ambitious target will be met before 2023, and if it isn't my estimates involving wind power would need to be reduced.

Generation capacity

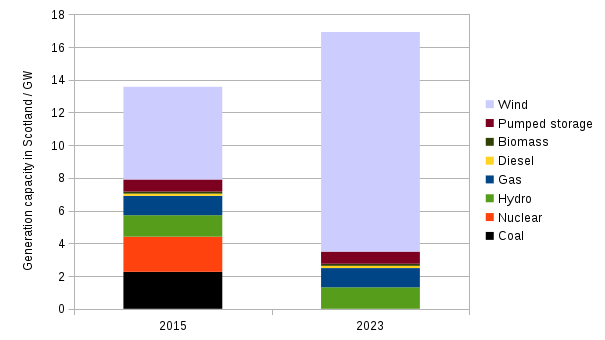

This graph shows Scotland's electricity generation capacity in 2015 and my estimate for 2023 assuming the Scottish Government's renewables target is met by new wind farms and all coal and nuclear capacity is lost.

Source: compiled from the Energy in Scotland 2015 Scottish Government report and DUKES 2015.

Some simple arithmetic tells us that overall capacity will have increased by 8 - 4.4 = 3.6 GW. On the graph, this corresponds to the removal of the black and orange segments at the base of the 2015 column, and expansion of the blue-grey segment at the top.

But there is of course a crucial qualitative difference between the 4.4 GW we are losing and the 8 GW we are gaining. Wind capacity of 8 GW is the maximum we can expect when the wind is blowing. In the UK capacity factors for wind farms are about 30%, so we can, on average, expect 2.4 GW from this extra 8 GW of wind farm capacity. This leads us to the question: will having an average of 2 GW less generation mean we need to import electricity on days of low wind?

Meeting demand

Averaged throughout 2013, the latest for which figures are given, demand was 3.7 GW. Scotland's peak demand is about 5.5 GW. This will most likely occur on a cold winter evening at around 6pm when people are returning from work. Although not stated explicitly, these figures can be estimated from the total consumption figures and seasonal variations given in Chapter 3 of EIS.

Electricity demand has declined in recent years, in part due to gradual improvements in efficiency (e.g. use of low energy and LED light bulbs) but there was also a noticeable drop in non-domestic usage due to the recession post-2008. I've not found any clear predictions for Scotland in particular, but according to the National Grid's Future Energy Scenarios report the GB grid's peak energy demand is forecast to rise from about 55 GW now to between 59 GW and 66 GW in 2030. With this in mind, and for simplicity, I'll use the above average and peak demand figures for Scotland in 2013 in what follows.

For 2015, the above graph's data shows that Scotland can supply 7.9 GW if zero energy is generated from wind. This assumes all non-wind sources are at maximum capacity and there are no losses. If we allow for 15% losses (see gross vs total consumption figures), and reduce capacity by another 10% to reflect reduced capacity due to faults and maintenance, then the supply available to meet demand is about 6 GW. So at present, even in this worst case scenario — zero wind, highest demand — Scotland can meet its own consumption and export 0.5 GW elsewhere.

For 2023, the non-wind supply figure drops to 3.5 GW, which becomes 2.6 after deducting for losses and other factors. About 0.9 GW of imports are needed to meet average demand, and 2.9 GW to meet peak demand.

Of course, these figures are the worst case scenario on windless days. In 2023, my estimated capacity for wind is 12.2 GW and applying the 30% capacity factor gives 3.7 GW and deducting 15% losses gives 3.1 GW. So total supply will be 5.7 GW which is enough to meet peak demand and export 2 GW on average.

Nevertheless, we'll have moved from a situation now where we're almost always able to export, to being dependent on imports at times of high demand and low wind. (I might come back to how often this might be in a future blog post.)

Change, but for better or worse?

I am not alone in coming to the conclusion that Scotland could well become reliant on some degree of electricity imports in coming years. The Institution of Civil Engineers arrived at much the same conclusion. But is this necessarily a bad thing?

Firstly, does the GB grid have sufficient generation capacity in years ahead? According to ofgem's Electricity security of supply report, the winters of 2015/16 and 2016/17 do give some cause for concern, though a number of measures should ensure a sufficient supply in all but the very worst case scenarios. From 2017/18 onwards, the situation improves as mothballed power stations are returned to service and new power stations come online.

From the point of view of the GB grid as a whole, Scotland's move away from electricity exporting to a position of balance with occasional importing makes some sense. In 2013, 28% of electricity generated in Scotland, some 14 TWh, was exported to the south of the GB grid. Whilst this may be of economic benefit to Scotland, it is wasteful in that energy is being lost along the hundreds of miles of wires. It makes sense to locate generation closer to the demand.

There are environmental benefits too. Longannet is an inefficient, coal powered station and its closure will significantly reduce Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions. Some may also welcome the fact that nuclear power is being banished from Scotland, though we'll still be dependent on the ones in England when importing and, to small extent via a 2 GW inter-connector, on the many nuclear power stations in France. The big downside of course is that the closure of these three large plants will involve the loss of many jobs. It is vital that action is taken to help those people affected.

There are some infrastructure improvements that would fit very well with the Scottish Government's renewables strategy, their politics and the overall needs of the GB grid. Specifically, the construction of more pumped storage facilities. These use excess electricity to pump water to a high level reservoir during times of low demand, and can later use that water to spin up turbines in a matter of minutes to meet large jumps in demand. At present we have the Foyers pumped storage facility at 0.3 GW, which dates back to 1896 for aluminium smelting, though much upgraded since, and the ground-breaking and mountain-hollowing Cruachan facility at 0.44 GW. I hope proposals to expand Cruachan or build a new one at Coire Glas are progressed.

I very much doubt the current Scottish Government's intention was for Scotland to become reliant on imports, and consqeuently more dependent on decisions made in England and Wales. Nevertheless, by prioritising the renewables target over replacing traditional power stations, that seems to be the end result. But, viewed across the GB grid as a whole — and for reasons of infrastructure and the environment — I have to conclude that the coming changes are, in the round, positive.